This year will mark my fifth year in recovery. I would say I have definitely encountered my psychic shift. It has all been by God’s grace, paired with a willingness to look in the mirror, talk honestly about the inside of my brain, and accept that I was never meant to do this alone.

What has changed recently? If I’m completely honest, my focus has shifted from recovery from to recovery to. I’ve used that phrase for the last couple of years because I knew I needed to move forward into life, shaped by this new way of seeing the world and my relationship to it.

I remain, in many ways, a walking paradox. I am many things at once. I am grateful and feel pangs of remorse on any given day. I wouldn’t change a thing, yet I would give anything for a do-over. These statements sound like they can’t exist in the same space at the same time, but who ever said the very being of a man is bound by the laws of physics?

The mantra of my recovery fellowship is from shame to grace. Many would read that as a point A to point B journey, and I suppose that’s partly true. What that view often misses is that we continue to need grace, and we continue to take inventory. In the Twelve Steps, the inventory begun in Steps 4 and 5 continues in Step 10. This is ongoing.

Every day in recovery is a spectrum of relapse into the illusion of independence. I may not fall back into my darkest hole, but each 24-hour period is still full of cocktails of fear, resentment, gratitude, peace, joy, and regret. I am a tapestry of what the programme calls assets and defects of character.

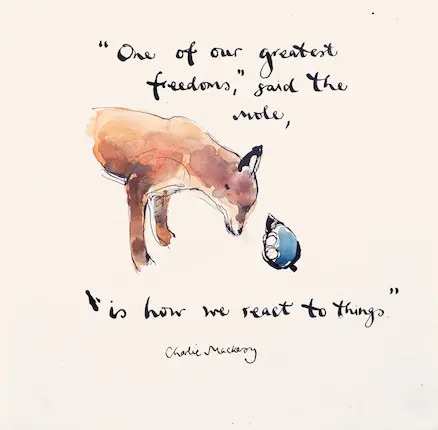

In The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse, the mole says to the boy that one of our greatest freedoms is how we react to things. Every day presents that opportunity to live in freedom. Until I accept that the only thing I can truly count on in this world is the grace of God, my inventory becomes that of a score-keeping Pharisee of self. With grace, it becomes a head-up, self-aware posture that recognises how a word, a look, or a deed affects others.

One of my biggest life skills is the ability to own my own shit before others do. I am still a smiling and loving pile of contrition. Honestly, the day I cease to be so is probably the day I fall back into my old delusions.

If my addiction is wedded to my illusory self, then I see it existing in much the same way Lord Voldemort endured throughout the Harry Potter films. My cycles of addiction split my soul into pieces, hidden away like horcruxes. For me, food, social media, tech doomscrolling, procrastination, and even permitted sexual behaviours can become places where my character defects feel nostalgic for the past.

Here’s a concrete example. Masturbation with the boundary of no porn or unfaithful fantasy is a permitted behaviour for me, yet I often need reining in. The muscle memory to ritualise it is deeply ingrained. With food, I can eat badly, gain weight, and quietly undo the wins of a life lived in recovery. My running, cold plunges, and hunger for outdoor adventure give way to eating at stupid times, buying larger clothes, and chewing Andrew’s antacids like they were named after me.

This week’s contradiction is this: I have desire and lust for my own partner. Instead of stepping out and initiating intimacy, I retreat into fantasy. I end up in another room, jacking off to imagination and euphoric recall of being with the woman I love. There’s something profoundly sad and lonely in admitting that I have all I need, yet still opt for a counterfeit sense of relief. I don’t feel overwhelming shame about it, but it continues to fuel a deep sadness.

When it comes to intimacy, I express love, affection, and longing. Yet years of feeling inadequate and fearing rejection pull me back into nostalgic fantasy, rather than the beautiful, participatory chaos of real connection. Call it what I want, but I’m living in the past, flicking through the “porn magazine” of my own biography.

Even here, there is gratitude. I long for her. I can honestly say I’ve never been so tethered in desire, love and fantasy to my own partner.

So what’s my feedback to myself? My recovery logic differs from that of an alcoholic, where sobriety is black and white: consume or abstain. That binary works for substance addiction. With process addictions, the reasoning is different. Food addicts still need to eat. Gamblers don’t need to gamble. Sex addicts don’t need to be celibate. The issue is discernment.

In SAA, we define our own abstinence. It isn’t fixed in stone, but it must be rooted in honesty. To thine own self be true.

This is why others remain essential to my recovery. I can’t afford to confuse privacy with secrecy the way I once did. Today, my self-reading tells me I am more emotionally open, reflective, and gracious. Yet I am still intimacy-avoidant, and I can’t change that alone or heal in a vacuum.

So nearly five years in recovery? It’s still one day at a time and my recovery is best done less about me and more about we.

This is where we talk , set another boundary and continue to take one day at a time.

God, give me the serenity. Grace always grace!