“Only by discussing ourselves, holding nothing back, can we stay in fit spiritual condition.”

— Bill W. As Bill Sees It

Over the last year or two, my Step Eleven, “maintain conscious contact with God,” and Step Twelve, “carry the message to others,” have brought me to a new kind of crossroads. I’ve had to face my need for ecclesia — a spiritual community — in a way that the rooms of SAA, for all their grace and connection, couldn’t fully meet.

I remain part of my home group. The relationships I’ve built there will always be part of my life. I’ll never graduate from recovery, and I’ll always feel the pull of purpose to love and serve in that community. But alongside that, I’ve felt a growing need for fellowship with Jesus people — not in place of recovery, but as a continuation of it.

The Twelve Steps became my map, not only toward healthier living but toward a more gracious and loving vision of the God who still remains mystery. And if one thing has become clear, it’s that God is inexhaustibly loving, forgiving, and kind.

You might think that means I should simply find a church and settle in, and you’d be right — it should be that simple. In my naïveté, I thought I could find a quiet fellowship with a safe, non-triggering environment where I could participate and belong. I met with the minister, shared my story, and we reached a mutual understanding that healing and restoration could include me playing songs during worship.

But the level of disclosure that recovery brings can be a tightrope for some. I shared my full story with this dear brother and was met initially with grace, understanding, and accountability. Yet when my involvement was later reviewed with the wider leadership, we were met with knee-jerk concern and a hard “no.” The decision was made that someone with my sexual sin history could never be deemed trustworthy to serve out front.

To be treated like a potential public risk or dangerous deviant as a result of my transparency left me with a mix of forgiveness and resentment to wrestle through. I do understand the horizontal consequences that come with the chaos we create in addiction — the broken trust, the hurt, the long shadows. This isn’t a pity party or a refusal to own my past and my part.

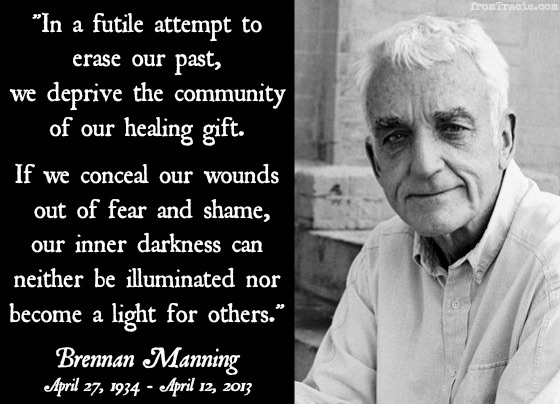

But this experience taught me something else: that it’s safer to stay under my rock than to risk darkening the door of another “godly community.” My hope wasn’t about taking a stage; it was simply about being welcomed and allowed to participate. The Bible is full of broken people used by God — not because of their righteousness, but because their human brokenness became the very space where grace could shine.

I’ve seen crowds cheer as murderers testify how Jesus met them in prison, and I say yes and amen to that. Yet somehow my own moral failure, expressed through the isolation of internet use, placed me beyond restoration in the eyes of some. Sexual dysfunction carries the most shame and controversy, so it’s two for two.

Isn’t it strange that Twelve-Step recovery communities often demonstrate a deeper understanding of grace than many churches? That experience showed me that my calling lies not behind a pulpit, but in men’s ministry — sharing my once-unspeakable story with the men who sit silently in pews, carrying their shame in secret because the “Sunday best brigade” offers no safe place to speak.

I understand that churches face real challenges in the aftermath of #MeToo and countless historic safeguarding failures. But the cosmic shift of the Cross — the declaration that grace has been extended to all — seems at odds with closed doors and cynical suspicion. The Church was meant to be an ER for broken humans of every kind. If we doubt that, we need only look at the people Jesus sought out.

The great Robert Capon once said:

“Jesus did not come to cure the curable, to reform the reformable, or to teach the teachable. He came to raise the dead, and by raising the dead, to make the whole creation new.”

In Twelve-Step recovery I’ve met men from all walks of life, including ministry. Many found in those rooms the grace and warmth they never found in church — a space where weakness becomes the doorway to love. In a world that keeps shouting “do more, try harder, be better,” they find healing in surrender, not striving.

I believe we’re living in an age where the world is beginning to see that we are all addicts of one kind or another — a planet full of broken people chasing dopamine highs, validation, and isolation behind curated profiles and identities carved by trauma.

It’s time for the Church to become the sanctuary and refuge it was always meant to be — a place where honesty is theology and truth is our currency.

As for grace and forgiveness, they’re already on tap. The flow began two thousand years ago, and that barrel will never run dry. In Jesus, God really has done for us what we could never do for ourselves.